Walking into Petco Park last Saturday, I smiled at the sight of many old and faded “Caminiti 21” T-shirts worn by fans who have treasured them over the years, and likely pulled them from their closet for Ken Caminiti’s induction into the Padres Hall of Fame. On the field, I talked with Nancy Caminiti, their three grown daughters and his parents. We had stayed in touch over the years, and mutually agreed that this induction was a good thing to recognize all Caminiti had accomplished and had meant to the Padres and community.

Sadly, Cammy was not there. The Padres beloved third baseman died in 2004, but the larger-than-life photo and video images on the scoreboard triggered chills and applause. It was reminiscent of those early days when, as broadcaster Ted Leitner put it, “The women wanted to look at him. The men wanted to BE him.” A genuine warmth exuded from the fans and from those on the field, including former teammates, coaches and fellow Padres Hall of Famers who relayed Cammy stories. We all laughed, sighed or even got a little teary-eyed as the tributes covered the different dimensions that made him special. Cammy would have been proud of his daughters. Kendall, the eldest, spoke on her family’s behalf, thanking the fans and the Padres for their love and support as her two sisters stood alongside her.

Looking back, I’m grateful to have played a unique part in helping bring Ken Caminiti’s story to the fans in my role with the then-new COX/Padres TV deal. Beginning in 1997, Cox would put 125 games on the new Channel 4 Padres and my assignment was to “connect the players to the fans.” I’ve written about this in my book, but here is a short reminder …

In the spring and summer of 1996, I was so caught up in a television project surrounding the Republican National Convention, I didn’t realize the Ken Caminiti sensation buzzing around the city. I hadn’t witnessed his stellar feats at third base or his powerful at-bats. Hadn’t heard about the “Snickers” incident in Mexico, nor seen his stoic presence contrasted with his sparkling eyes and smile in the dugout or off the field. These were all part of the Cammy mystique that had captivated a community of baseball fans. But when it looked as if I would be involved in the new COX/Padres television venture Channel 4 Padres, I sat on my mother’s couch and watched the Padres beat the LA Dodgers to clinch the National League West Division. Ken Caminiti became front of mind.

The first time I met Ken was that fall at a Padres’ awards banquet. I remember the crowd around him, and how quiet he was — almost uncomfortable with all of the attention. I wouldn’t come to understand that reticence, or him, for a few months.

One of my primary missions was to help the fans get to know the players as people, not just “guys in a uniform.” Ken Caminiti, an obvious choice for our first profile, had just won the National League MVP award and was rehabbing from shoulder surgery. The big question: Would he be ready for Opening Day?

The Padres public relations staff explained the situation to him, and with his approval, we planned a trip to his offseason home in Houston. A few people who knew Ken well suggested, “He’s a quiet guy, so good luck. He doesn’t talk much, and don’t ask him about his drinking problems of the past. He won’t want to talk about that.” Thanks for the advice, I thought. I’ll take it from here.

In early February 1997, I traveled to Texas with Mike Howder and Tim Young from the Padres media department. I had done my homework: reading what little had been written about Ken Caminiti; I had looked at some of the Padres’ music videos highlighting him; and had asked people about him. I mapped out my questions, creating enough of a guideline, based on facts and my own curiosity to be sure I wouldn’t miss anything.

On Feb. 4, we arrived at the gym where he was doing his rehab, following his shoulder surgery. We put a small microphone on him and followed him through his routine. I asked about his progress, and he demonstrated how far he had come by throwing a ball or lifting his shoulder, comparing it to his starting point. It was clear how far he had to go to be ready for the season.

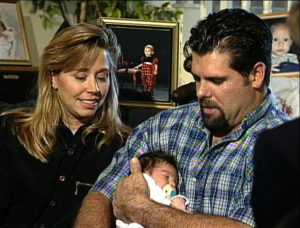

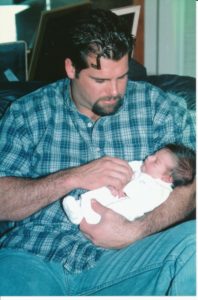

His home was comfortable, with pictures of family and a dining room table filled with baseball memorabilia from people who wanted autographs. His wife, Nancy, and three daughters were there, too — the youngest only a week old. We set up in the living room with just one camera and a few lights. He wore a blue- and white-plaid shirt and jeans.

I started from the beginning of his life, and as we went along, I could tell that he had much inside him. It wasn’t that he didn’t like to talk; he just seemed to need time to think in order to express himself. The rush of the typical pre- and postgame interviews was not necessarily his comfort zone, and that might have been why people thought he didn’t have a lot to say. Given time, I discovered, he would open up. A question about the relationship with his parents led to talking about his rebellious times as a teenager, challenging times in the early part of his career, and his faith. While referencing his special year of 1996, our dialogue went like this:

Jane: Do you have a sense of why this was your year?

Ken: I don’t know. I accepted the MVP award a couple nights ago, and part of my speech was God gifted me this year, and He really looked after me.

Jane: Tell me about your relationship with God.

Ken: Well it’s been a rocky one for me cuz in ’87-’88 I asked Him into my heart, Jesus Christ, but I didn’t do it for all the right reasons…”

While my questions were simple, his answers revealed much. I sensed during the interview, this was going to be something special. Had he not brought up the subjects I had been “warned” not to broach, would I have brought them up anyhow? Probably. How could I cheat him, his story, or the viewers of something so personal, but significant? I followed not only his lead, but also my intuition, delving into both obvious and sensitive topics. In Ken’s case, just asking about his year opened the door to something that was in his heart. No matter how much I prepared, just listening and caring showed him respect, and made him feel comfortable to express himself. In the bigger picture, it was the unexpected prelude for what was to come.

We completed the sit-down interview with Nancy beside him, and I met his girls, Kendall, Lindsey and newborn Nicole, who was so tiny in his muscular arms. I commented on how he had an All-American family.

“All American.” He laughed. “With the toys, the blind dog knocking over the lights. Yeah, All-American!”

Ken took Mike, Tim and me to dinner that night at Papa Deaux’s. As we walked into the restaurant, ESPN was airing the recorded ESPY awards program where Cammy was accepting the honor for Best Baseball Player. People at the restaurant did a double take when they saw him — a former Houston Astro, the NL MVP with the Padres — on TV, yet standing there in person. No question, he exuded an air of distinction, even in his plaid shirt and jeans.

When I returned from Texas, I shared about the in-depth interview, which prompted the green light to produce the new series, One on One. Ken’s was the leadoff show. I felt it important to supplement his story with details. So, at spring training, I interviewed his personal trainer and saw Cammy in uniform, counting the days until he would be — hopefully — ready for the season. I also believed it was important to hear from his parents, to see where he grew up, went to school, and began his athletic career so I flew to San Jose to see where it all began for Ken Caminiti.

His childhood home, where his parents still lived, was modest and in a fairly middle-class neighborhood. They welcomed us and offered more insight about their son. They gave me a bag of home movies and pictures, and pointed out the cul-de-sac where young Ken rode his bike. A stop at his high school and San Jose State University provided more content and texture.

As I wrote my first 30-minute biography, trying to fit it all in, I was determined not to leave out anything important, including the sensitive aspects of Ken’s struggles with alcohol and his faith. The program was a hit. People commented about the candid interview, about seeing the pictures and learning who Ken Caminiti was, and how he’d evolved with the team and in life. At the 2016 induction, former teammate Trevor Hoffman talked about how getting a “nod” from quiet Cammy was like getting a big bear hug. After Ken saw the first show in 1997, we happened to meet. When the subject of the show came up, he gave me one of those nods and a “thank you.” I’ve always considered that my big bear-hug bonus.

Ken Caminiti was truly loved, and he loved San Diego. He would go on to be a hero in the 1998 season in which the Padres played the New York Yankees in the World Series, but after the ’98 season, the Padres embarked on a “rebuilding” phase. He was a free agent. He signed with Houston. Fans would see him when he played in San Diego for Houston, and then Atlanta. He always received a round of applause when he returned to San Diego, but things would not be easy for him.

What we didn’t know in 1997 — and would not find out until after he retired — was that part of his “wow” factor while playing with San Diego was not just natural brute strength. Ken Caminiti shocked the sports world in 2002 when he told Sports Illustrated that he had taken steroids during his MVP 1996 season and beyond, and that he thought others in baseball had too. That revelation — considered the first public admission of anabolic steroid use by a professional baseball player — rocked Major League Baseball, and contributed to the eventual exposure of Performance Enhancing Drug use in the sport, which launched a congressional investigation, and eventually, a more defined PED-use policy in baseball.

In 1997, however, no one was talking about steroids, PEDs, or human growth hormone, so it did not even occur to me to ask Ken what specifically he was taking as part of his fitness regimen, or to even think that he might be doing anything that would cause him problems later on. Even so, his leadership in the clubhouse, as his teammates explain, his “throwback” mentality of playing through pain and wanting to be in every game, and his indisputable mystique yet genuine connection with the fans combined to make an indelible impression in his four seasons playing for San Diego.

The last time I talked with him was at spring training in 2004. I could see in his eyes he wanted so much to be “OK” and said he wanted to work with the Padres again. He gave me a hug, and I said I hoped things worked out, and that I would see him back in San Diego. Sadly, his struggles with addiction took their toll and he died that October.

In the spring of 2005, Ken Caminiti would have been 42. The Padres honored his memory at a pregame ceremony. Now, in 2016, he has been inducted into the Padres Hall of Fame, which I applaud. I have learned a lot in my 16-plus years around the game and telling athletes’ stories. These human beings have weaknesses and vulnerabilities, like all of us, even with their immense work ethic and heroics. While we have “clean” heroes, including his contemporaries Tony Gwynn and Trevor Hoffman who also are in the Padres Hall of Fame, I truly believe Ken Caminiti belongs there too. Although he was admittedly part of the Steroid Era, he was also instrumental in bringing it to light. Perhaps this is why, while few would condone PED use, we can forgive and accept it more readily because his explanation came with honesty and humility. How common is that? And aren’t those characteristics we would want emulated as much as teamwork, hard work, charisma and charity?

Ken Caminiti will forever be part of a magical time in San Diego, part of a special collective memory, and part of my journey. There’s much to learn from how he played, how he lived, how he loved and how he battled.

To read more of the backstory from my experiences and the transcript of the 1997 “One on One” program, visit www.JaneMitchellOneOnOne.com for a copy of the book.